Once you figure out how to create an income in retirement, it’s time to address another question: how much can I take from my retirement savings annually without running out of money in my lifetime?

There is a concept well-known in the financial planning industry called a “safe withdrawal rate”. Some of the risks associated with retirement include the length of your retirement, inflation rate, and whether portfolio returns will be favorable or not.

Like everything in personal finance, there is no one-size-fits-all with your retirement strategy. But this concept helps give you a sense and a measuring stick to use throughout retirement to ensure you stay on track.

The concept that has become widely adopted is known as the ‘4% rule’.

What is the 4% rule?

The 4% rule is a guideline suggesting that retirees can withdraw 4% of their retirement savings annually to ensure their money lasts at least 30 years. This is assuming that the retiree has their savings invested in 50% stocks, 50% bonds. However, it’s essential to consider individual circumstances.

For example, if you have $1 million in savings, you could withdraw $40,000 each year, for 30-years, and likely be more than ok. Although this strategy is a solid starting point, you need to create a plan that is applicable to your own situation. Don’t just follow the crowd and feel like you can never take more than 4% per year or else you are screwed.

Don’t let this discourage you either, “A million in savings is only good for $40k a year in retirement! I’ll never make it…” Flexibility is key here. Using multiple sources of income can get you to your needed income level each year.

Some years you might need to withdraw more than 4% annually. For instance, you plan on taking a higher percentage out of retirement accounts early on, so you can delay your social security benefits, maximizing your guaranteed income. But if you are constantly ramping up your withdrawals in retirement, spending $150k per year when you thought you only needed $100k, history has shown us that’s a risky game.

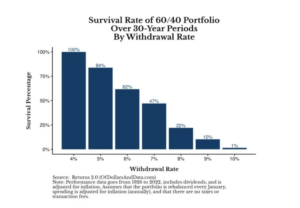

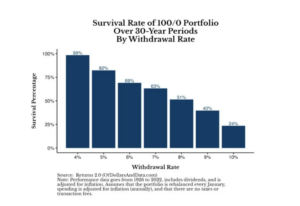

These are great charts from Nick Maggiulli highlighting the survival rate of portfolios over 30-year periods by withdrawal rates using historical returns from 1926 – 2022:

For those that know Dave Ramsey, he recently went on a rant trashing the 4% rule claiming people should confidently take 8% per year from their portfolios.

Surprisingly, the numbers were better than I expected based on Nick’s analysis. But still, for me, this is dangerous to put out there to the everyday investor. In order for Dave to achieve the 12% per year on average of investment returns he boats about over a 30-year period, the portfolio has to be in 100% stocks. As a result, you will be putting up with significant drawdowns, maybe even years of 20-30% declines, multiple times during your retirement.

You’re 70, relying solely on your retirement savings, and suddenly, your $1 million turns into $700,000 in 12-months, and you are still taking money out. How are you feeling? Do you have the stomach and emotional restraint to not lose your shit and question everything? For most of us, that’s a nightmare. Don’t get me wrong, you still need to take risks with your retirement savings while retired. If you need to take a higher withdrawal rate (>=6%) from your savings, then you should allocate more of your investment into stocks.

Stocks also serve as a hedge against higher inflation while you are retired.

Again, each strategy is different and presents different risks and tradeoffs, there is no right or wrong answer. Create a plan that feels right to you.

But creating a plan in general creates peace of mind and structure once you do retire. There’s even an argument to be made that most of us will not even come close to running out of money in retirement 😉

–

Disclosure: This material is for general information only and is not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

- All indices are unmanaged and may not be invested into directly.

- All investing includes risks, including fluctuating prices and loss of principal.